My penultimate round of focus groups with undecided voters took place in Cardiff, where many people’s perplexity over the decision at hand was not turning not into enlightenment but exasperation. Among the many words people used to describe the contest so far (“unreliable”, “unrealistic”, “uninformative”, “not that interesting”, “unnecessary”, “a quagmire”, “a lot of bullsh*t”), by far the most common was “confusing”.

The campaign “is not helping one bit. It’s just, ‘this is going to happen’, ‘no it’s not’.” Though practiced in taking politicians’ words with “a pinch of salt”, there seemed to be no firm basis on which to work things out. “How come you get so much difference in the sums they talk about?” “You see the same figures but you hear different facts about them. They’ve got this £350 million figure but remain say it’s nowhere near that. So who do you believe?” “There’s nothing you can hang your hat on.”

Even though people discounted the hyperbole from each side, for some people it had had the effect of seeming to raise the stakes without making anything any clearer: “We’re frightened. Well, I’m frightened of what will happen to the country if we make the wrong decision.” The fact that it was “one-time only” and therefore “a bigger deal than a general election” only made things worse: “It’s a proper dilemma.”

Some hinted at the real problem: that they were having to work a bit harder than usual. “It’s so hard to become informed enough to make a decision. It’s highly complex, life is very busy. You’ve got to be really in-depth and understand the nitty-gritty;” “You need to know more about politics to vote in this than you do in a general election. Then you can vote as your family did, or because of your background, but with this it’s not that simple because we’ve never done it before.”

*

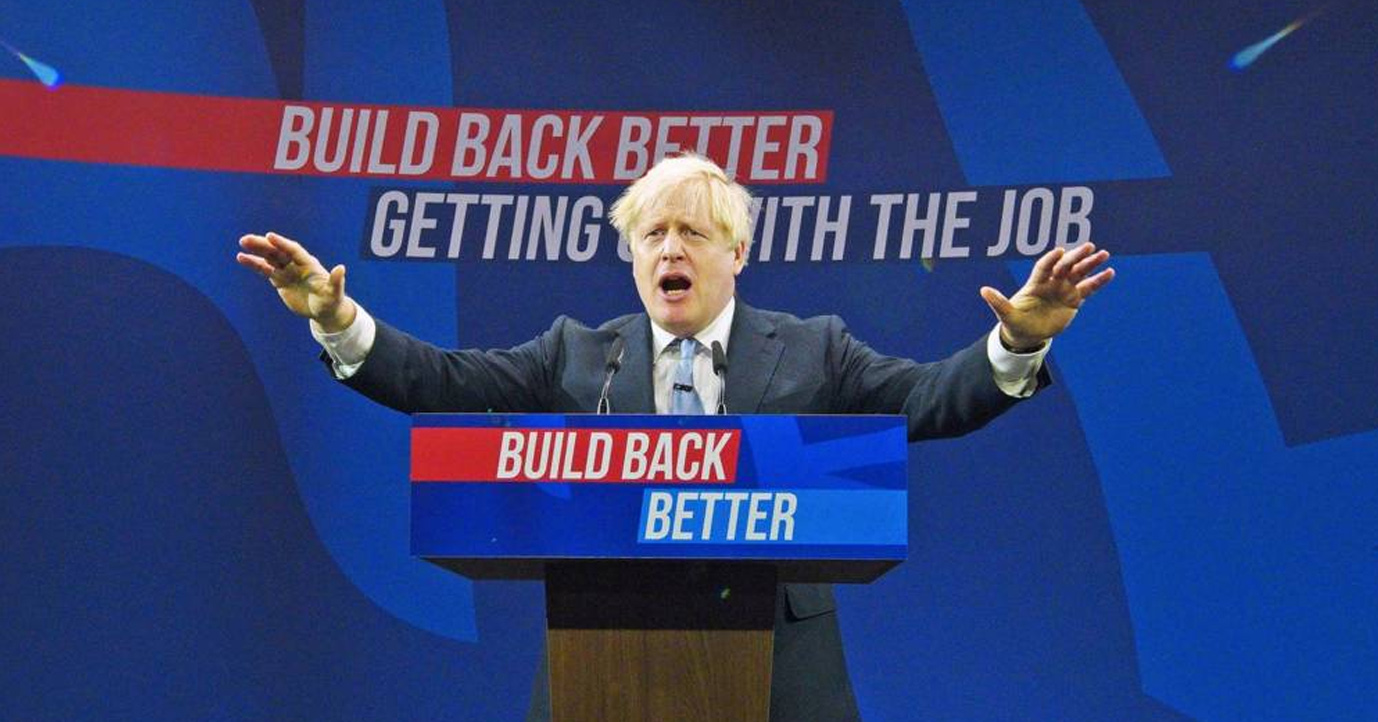

The absence of familiar labels continued to add to the confusion, as did the fact that one party seemed to be dominating proceedings. On both sides of the Brexit debate, “all the opinions we are getting are from people in the Conservative Party” (indeed it felt to some “more of a leadership battle in the Conservative Party than anything else”, not least because “Boris was undecided until a couple of weeks ago”). Even Sir John Major had got in on the act with his interview on The Andrew Marr Show: “He said he didn’t have anything against Boris but he’s getting the digs in – ‘court jester’.”

Lifelong Labour voters in particular found all this disconcerting and rather off-putting. Jeremy Corbyn “could be significant but for some reason he isn’t;” he “blew up for a little while but then he kind of disappeared;” “He’s been rubbish. He’s left it to Alan Johnson. But he’s the leader of the Labour Party – he ought to say a bit more than he is.” What accounts for Corbyn’s reticence? “He’s not strong enough. He did a U-turn. That’s why he’s stayed a bit quiet;” “From what I gather, it’s because he hasn’t made up his mind. He hasn’t come out and said ‘I want to stay’, at least that I’ve heard.”

The absence of a strong lead from their party made it harder for some Labour supporters to back a campaign that they identified strongly with David Cameron: “If I voted to remain, it would feel odd voting with the leader of the Tory party;” “I don’t know if it’s his face, but I don’t trust Cameron.” Then again, “it seems the leave lot are all kind of right wing”, and if Cameron were to lose, “after the referendum they will vote to get rid of him and we’ll be left with Boris, God help us.” Would that be so bad? “Oh God yeah, he’s an absolute pillock… I don’t know if the rest of the world would take us seriously.”

*

If politicians were not really helping with the decision, who else had been weighing in? “The Conservative Party has got Eddie Izzard on board”. Unlikely, but go on. “He was on Absolute Radio this morning telling everyone we wouldn’t be able to use those NHS cards abroad.” What makes people worth listening to, or otherwise? “I would trust the one who hasn’t got a horse in the race.” Most third parties seemed to be pointing one way: “I haven’t heard a non-political expert say anything other than stay. Stephen Hawking, the Governor of the Bank of England…” Not that this was always convincing: “Hawking is a clever chap but what’s he got to do with politics? He looks at the stars.”

*

One independent expert who did carry some weight, particularly with women, was Martin Lewis. Only the most determinedly cynical questioned his impartiality; for the rest, “he’s good. He tells it as it is;” “he gives you the facts;” “I trust what he says more than anyone else.” The groups watched extracts from his recent video, in which he explained that “there are no facts” and that “anybody who tells you they know what will happen if we leave is a liar”. If this did not help a great deal, it was at least a comfort to our participants that he shared their view of the evidence: “What he said was what we all just said.” It also helped expose the shrill assertions from the rival campaigns: “So how does Cameron know a hundred per cent, or Farage?”

Lewis’s conclusion, that he felt leaving the EU carried the greater risk and uncertainty, clearly chimed with several in the groups: “If I had to vote now, after watching that, I think I’d stay in.” This was perhaps all the more the case because of his insistence that he was not campaigning (which also helped him avoid the Neutrality Paradox, whereby sources regarded as impeccably impartial start to be seen as biased as soon as their independent analysis leads them to a view). His balance-of-risk approach also hit home: “I really hate my job. I would love to go in tomorrow and say I’m going to leave and become an actor. I could become the next Doctor Who. Or I could fall flat on my face and lose my pension. It’s the same with the referendum. Do I want to take the risk of it all going tits up?”

*

The ITV debate programme featuring David Cameron and Nigel Farage, which several in the groups had watched, had been rather less illuminating. If they had enjoyed seeing the audience in combative mood, they did not feel any the wiser for the experience: “They knew the questions and had the answers prepared. And when they’re asked a proper question they don’t answer properly.” Few thought a head-to-head debate between Cameron and one of his Tory rivals would clarify much: “It would just be a slanging match, speaking over each other.”

*

The groups were shown the two campaigns’ rival “pledge cards”. The leave list, “guaranteeing” that Britain would pay £350 million a week and that “uncontrolled EU migration” would continue felt harder-hitting and more tangible to some, though it also exposed that the campaign could make no pledges about the future.

The remain guarantees, as launched by David Cameron and Sadiq Khan, prompted some questions (“What is the European Arrest Warrant?” “Would we lose it if we left?”) The most intriguing claim, if the most puzzling, was that Britain would have a “special status” in Europe. Still, “I’m not sure what that special status one means. But if that counteracts some of the argument for leave, let’s hear it.” Any ideas? “I think it means special status for David Cameron. When he gets chucked out by the Conservative Party he will get a job in Europe.”

There were vague memories of the February renegotiation: “He got some concessions but he didn’t get what he went for. I can’t remember what he got but I remember that.” Well, for example, what if we could be part of the single market, have free movement of people albeit with migration to the UK, stay out of the euro, not be part of the Schengen no-borders area, and not have to contribute to Eurozone bailouts or accept migrant quotas? “Better.” “Brexit-lite”. “But what’s the likelihood of having something like that?” Perhaps the remain campaign should have had a different emphasis.

Still, the bailout exemption was not wholly reassuring. “Turkey and Albania will join and we’ll have to pay more money in, because they haven’t got a pot to piss in.”

*

The groups thought immigration was by far the dominant theme of the leave campaign (“apparently everyone from Turkey is coming here”). They had noticed several recent interventions on the subject, including Boris’s warning that Britain’s population could rise to eighty million: “He’s got a point. We’re an island. We can’t take all these people.” Immigration was a big concern for many, including those who had regular personal contact with migrants: “As a health visitor I work with a lot of East Europeans and minorities from outside Europe, and in a lot of the jobs they do like cleaning they are exploited, though it’s still better than what’s going on over there. But they do undercut people, especially in building, and that does cause problems.”

Even so, some worried that the theme was not being handled responsibly, particularly by UKIP. “Nigel Farage and his lot don’t separate migration, immigration, asylum seekers, illegal immigrants – they lump them all together;” “There are people in poorer areas, in poorer housing, and he just incites things. He tries to blame all those problems on immigration;” “There’s an ugly group who want to come out for ugly reasons, who say ‘they’ are responsible for all the problems in the country and ‘they’ should stop coming in. It’s rearing its head at every opportunity”.

Yet Farage’s speech, highlighting the events in Cologne on New Year’s Eve and warning of the consequences of introducing large numbers of young males “from countries where women are at best second class citizens”, sharply divided both the men and the women between those who thought he was playing the race card (“That was horrific – the stupidity of the man, saying if we stay in the EU we’re all going to be raped in the street”) and those who thought was highlighting an uncomfortable truth.

As in previous discussions, the doubt was whether leaving the EU would, in practice, mean smaller numbers of people coming to Britain. For some, the fact that only half of the UK’s very high net immigration came from Europe did not give much confidence on this front: “Half comes from the EU and half from the rest of the world. If we’ve got control over that half, why aren’t we controlling it more? If we can’t do it now, why would we do it after?”

*

A related subject was the powers Europe had to prevent the deportation of foreign criminals, highlighted this week by the leave campaign. This was agreed to be a problem: “The EU has got so many ridiculous laws and regulations. The out party is saying we can dispense with the nonsense that comes out of Brussels and get back to common sense.” The hesitation was that the rights enforced by the EU, though sometimes galling, were often quite useful: “If we got out we would be stuck with a Tory government. At least if we’re in the EU, it’s not solely them making the decisions.” But the question of rights and sovereignty was not straightforward: “I want them to keep an eye on British politicians, but I don’t want them telling British politicians what to do. Which puts me in a quandary.”

*

Though most had come across the claim that EU membership cost Britain £350 million a week, most also knew the figure was heavily disputed. The argument that money spent by Brussels could be dispensed by the British government instead only cut so much ice in Cardiff, where people had benefited from EU-funded roads and other infrastructure, not to mention agricultural subsidies (“you never see a poor farmer, do you?”) Wales had “done quite well – it’s something like £79 per person per year”. If this would theoretically be available from Westminster in the event of Brexit, it might well fail to materialise in reality: “I think less money would find itself in Wales than in parts of England… Subsidies could be the same or they could be a fraction.”

More broadly, David Cameron’s claim that Brexit would be like putting “a bomb under the economy” was regarded as the latest piece of frantic alarmism (“there have been plenty of recessions when we’ve been in the EU. There might be one if we leave but there might be one if we stay”). The warning from Roberto Azevedo of the WTO of risks to trade sounded to some like more of the same (“He’s not going to be short of a penny or two. He’s probably looking at big business, but if you look at small ones, they say the EU costs them more and causes them problems”), but not everyone was dismissive: “He’s the Director General of the World Trade Organisation, he knows what he’s talking about. He certainly knows more than Boris Johnson.”

Most agreed, though, that leaving the EU would hit the economy, at least in the short term: “I think if we go out it will take a while to settle because people will be unnerved.” As for the longer term, the debate was hard to keep track of. “Mortgage rates would go up if we leave. Or is it if we stay? One or the other.”