The Conservatives lead Labour by 34% to 30% in this week’s Ashcroft National Poll, conducted over the past weekend. The Tories are up one point since last week and Labour are down three. The changes are within the margin of error, suggesting that the parties’ national vote shares remain very close. UKIP are unchanged at 13%, the Liberal Democrats up one point at 10%, the Greens down two points at 4%, and the SNP up two points at 6%.

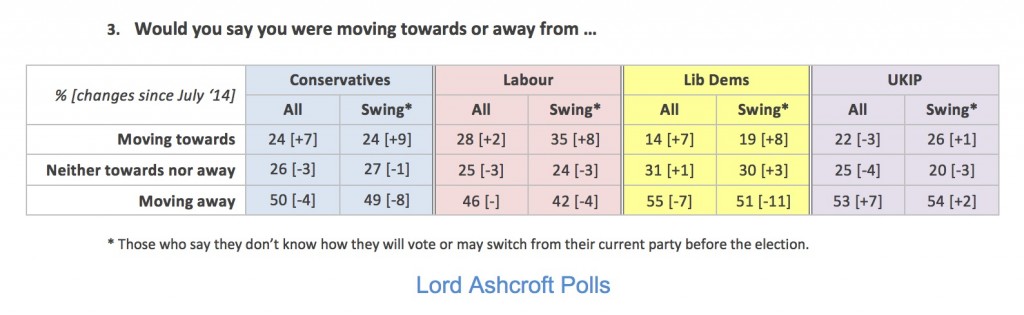

With just over two weeks to go to election day I asked people whether they were moving towards or away from each of the main parties. Swing voters, who say they don’t know how they will vote or that they may yet change their minds, were more likely to say they were moving towards Labour (35%) than the Conservatives (24%) or the Lib Dems (19%). A higher proportion of voters said they were moving towards the three established parties, and fewer said they were moving away, than was the case when I last asked this question in July 2014. The reverse was true for UKIP: 22% said they were moving towards the party (down three points), while 53% said they were moving away (up seven points). However, UKIP’s own supporters were the most enthusiastic of any party’s: 92% of UKIP voters said they were still moving towards their party, compared to 78% of Labour voters, 75% of Tories and 64% of Lib Dems.

**********

This week’s focus groups with undecided voters took place in St Austell & Newquay, where the incumbent Liberal Democrats face a strong challenge from the Conservatives, and Plymouth, with participants from the Moor View constituency where my polling has found UKIP as the main opponents for Labour. (Plymouth was also the only venue so far in which we have come across a ‘Vote Communist’ billboard).

The St Austell participants recognised the constituency as having been a yellow stronghold (“the Lib Dems are all over the place”) and many had previously voted Lib Dem because of good local MPs. Stephen Gilbert? “David Penhaligon”. Most thought Mr Gilbert had stepped into the tradition of standing up for the area: “the pasty tax, he sorted that out. They wanted to charge you extra for a pasty!” But they knew things were tight this time, with Steve Double, the Conservative candidate and former Mayor also enjoying a good reputation and a high profile, supported campaign visits from senior figures: “The Conservatives have thrown quite a lot of money at it. They’ve all been down here.” Interestingly, the Lib Dem literature was making a virtue of the closeness of the race: “There was a weird thing on the leaflet – it had the odds on him winning and said he wasn’t the favourite, so he was saying ‘I need your vote’.”

For most of the Cornwall participants, local factors tended to pull people towards the Lib Dems and national factors towards the Conservatives (“I’ve decided the Tories are the only people who can run the country efficiently”), with some exceptions: “I’d like to vote Labour every time, so here I vote Lib Dem to keep the Tories out.”

Over the Tamar, one prominent national issue, Trident, was also a big local one. Any suggestion that Labour might not be completely committed to a full replacement sounded dangerous: “I’ve already changed from Labour because he wants to get rid of the defence. I work on the V-boats”.

**********

Most of the participants had only the haziest recollection of any of the details of the parties’ manifesto launches, even though they had dominated the week’s news. To refresh their memories we showed them edited highlights of each leader’s launch speech.

The reaction undermined the polite fiction, often heard in focus groups, that people will read the manifestos and consider the detailed policies before deciding (“I’d have turned off before the end of that”, one admitted). As usual, the first comments on the clip of Ed Miliband were about him rather than his proposals. “How did he get in instead of his brother?”; “he’s not leader material”; “he gives me the heebie-jeebies, I’ve got to be honest”. But the observations were by no means all negative: some thought he had shown himself to be stronger than expected (“since campaigning has kicked off he has done himself a lot of favours. He stood up to Paxman”) and there was some evidence that people who were deciding to vote Labour were reconciling themselves to the choice of PM this implied (“he’s not leading the country on his own, there is a team of people. He’s not making decisions by himself”).

Some of the proposals appealed to our participants, particularly on the minimum wage and zero hours contracts, but some who ran small businesses were worried: “Unemployment would go up. I own a zoo” (of course!) “and I’m looking at employing two people, but with fixed contracts and a higher minimum wage I’m not sure I’ll be able to. I won’t be able to guarantee the hours month on month but over the year I’d look after them”; “it’s the same in my pub when we employ people for the holidays. I might only have eight hours for them this week but next week I might have fifteen.”

People’s biggest overall question about the policy package – especially employing new doctors and nurses and cutting tuition fees – was whether it could be afforded. Miliband’s emphasis on deficit reduction in his speech was not enough to overcome people’s longstanding suspicions about Labour on this score: “he’s about spending more money. He’ll run us into debt again”; “He doesn’t say how he’s going to pay for it”; “They left that note, ‘there’s no money in the pot’. I saw it on Facebook”. There was also the inevitable feeling about a list of promises that felt a bit too good to be true: “he’s saying it as if they will do it all straight away but you know it would take years, if it happened at all.” What do Labour still need to do to win people over? “Prove they’re different. Convince people that they mean it that they won’t repeat their past mistakes.”

**********

David Cameron’s manifesto commitments led some to ask “what about the last four years, why didn’t you do it then?”, or to think the proposals did not seem to match the government’s actual priorities, according to their own experience: “he says no rise in train fares, but we’ve got the most expensive trains in Europe. Shouldn’t someone have had their eye on the ball already?”; “he says everyone will be able to get a doctor’s appointment seven days a week, but I called this morning and the next appointment is in a fortnight, and that’s under his government.” Some were also worried about the tone on issues like welfare reform: “it’s as though they’ve taken all the non-racist stuff from UKIP and stuck it in the manifesto”. However, there were popular elements, including help for first-time buyers, the tax-free minimum wage and, for most, the inheritance tax pledge.

As with Labour, the long list of promises prompted a few to ask “where’s the money coming from?”, but others thought the Tories’ record of trying to get to grips with the public finances had given them more credibility on this front: “he was saying we’ve got to continue on the same path with austerity. You can’t spend what you haven’t got and you can’t always have everything you want in life. I don’t think he’s promising anything he can’t deliver, whereas I think Labour are.” Some also felt the Conservative package seemed more modest, and therefore more believable: “they are little things that could be achieved. Miliband was talking about big things that may be achieved.”

However, for some who had felt themselves the victims of the government’s policies there was no going back to the Conservatives. “I work in the justice sector and I was a cut. I’m going to vote wherever Chris Grayling is not”; “I work for Royal Mail, so I got privatised. Now I’ve got to work for a living and it’s a killer.”

Most in the groups thought well of Cameron himself: “when he says stuff, it sometimes comes across that he actually means it”; “he has an air of authority. It doesn’t mean I support him but there is an element of leadership”. Several in both venues also noted approvingly that the Camerons often take their holidays in the south west. Does that really matter? “Yes, it’s good! It brings other people down here.”

**********

The Lib Dems’ manifesto launch did not produce a great deal of excitement. Most thought Clegg was light on specifics, and they took the policies he did outline with a bigger than usual pinch of salt, given what they regarded as the party’s record on keeping promises. People were also doubtful about Clegg’s central theme, that the Lib Dems would “add a heart to a Conservative government and a brain to a Labour one”: “He told us nothing really. He just said ‘vote for us and we’ll make it all fine’.” Whatever the virtues of their local MPs, the Lib Dems had not convinced many of these participants that they had “what it takes” to be a significant influence at a national level. “It’s the biggest chance they’ve had to make a difference, but they’ve…well…” Yes? “Well they’ve f***** it up, haven’t they?”

Nevertheless, most liked Nick Clegg (“he’s got a good heart”), thought he came across well in debates, and preferred him as a potential coalition partner to the SNP (“I wouldn’t trust that Nicola Sturgeon, she’s got very thin lips”).

**********

Doubts about Labour’s commitment to renewing Trident did not have the effect of pushing our Plymouth groups towards the Tories. Most of these participants had voted Labour in 2010, and for them UKIP was the alternative attraction. Nigel Farage’s presentation of the UKIP manifesto was the only one of the four to elicit nodding and even cheering. The enthusiasts regarded most of what he said as obvious common sense, and argued that by talking about cutting international aid and scrapping EU contributions he had explained how his ideas would be paid for: “It sounds doable and he says how he’s going to get the money”; “not letting foreign criminals in is a no-brainer.” But if all this is as simple as Farage says it is, why has it not already been done? “They’re afraid, they don’t want to be accused of being racist. But other countries do, like Australia”. Farage “says what the normal man in the street would like to have said. Most of what comes out of his mouth, a lot of us have said at some point.”

But the UKIP leader’s taste for controversy was not universally admired: “when he says something and gets in trouble he thinks, great, I can take it one stage further. He’s like Katie Hopkins.” His policy programme also had its detractors: “It’s as though he’s taken things from the Conservative and Labour manifestos and put them into a package that would cut us off from the rest of the world.” Some of the younger participants debated whether the typical UKIP supporter was “a tweed-jacketed Tory who hates Europe” or “a skinhead with a baton”.

Even the biggest Farage fans acknowledged when pushed that they might be suspending their disbelief somewhat, given that he is a politician: “If he got into power, I wonder how different he would be then”. The point is that “he hasn’t let us down yet.”

But for those most inclined to vote for the party, “it’s not just about getting UKIP into government, it’s about getting them seats and a voice. They can build on that. They’re shaking it up.” What about the idea that by switching from Labour to UKIP you could let the Tories back in? “I would vote for who I wanted to vote for. That’s something for Labour to worry about.”

**********

Very well. But what do you suppose is the Prime Minister’s favourite TV programme? “I reckon he’s got an EastEnders fetish. That’s how he gets his idea of what ordinary people are like.” Mr Clegg? “Countryfile or Antiques Roadshow, something soft and fluffy. Or whatever his wife has told him they’re watching.” Mr Miliband? “Panorama”. And Mr Farage? “He would only watch British comedies. Only Fools And Horses; he models himself on Boycie.”