Labour and the Conservatives are tied at 33% in this week’s Ashcroft National Poll, conducted over the past weekend. Both parties are down since the last ANP two weeks ago (Labour by one point, the Tories by three); UKIP and the Lib Dems are each up three points at 13% and 9% respectively, with the Greens down one at 6% and the SNP unchanged at 4%.

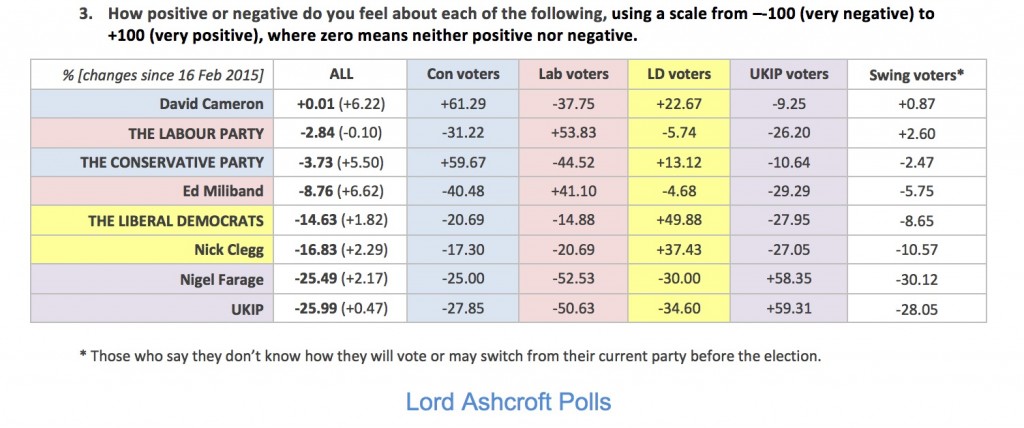

Most parties and leaders were given better marks than was the case when I last asked people to rate them in February. David Cameron was the only one to receive an overall positive score (albeit just +0.01 on a scale of -100 to +100), and has the highest ratings of any leader among his own party’s supporters. Nigel Farage and UKIP were given significantly lower ratings by women (-33.49 and -31.09) than by men (-17.13 and -20.67).

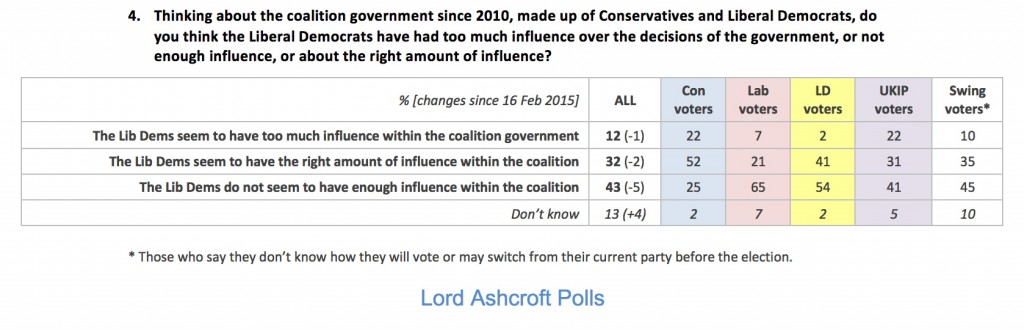

Just under one third of voters thought the Lib Dems had the right amount of influence within the coalition; 43% thought they had too little, while 12% thought they had had too much. It was notable that Conservative voters did not think their coalition partners had had a disproportionate say in government: more than three quarters of Tory voters thought the Lib Dems had had either the right amount of influence (52%) or not enough (25%).

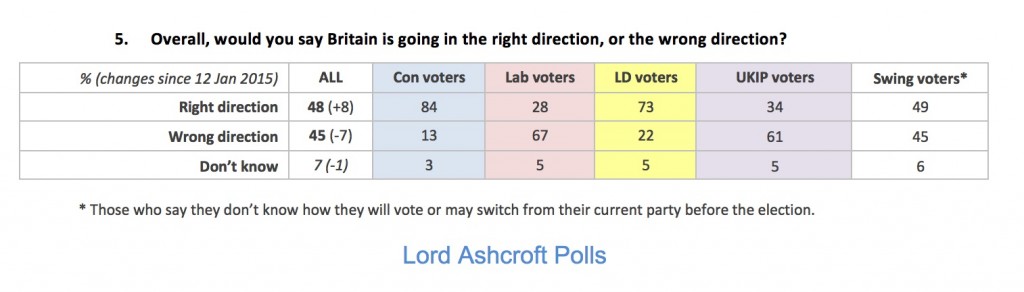

Overall, just under half (48%) thought that Britain was “going in the right direction”, an increase of eight points since I last asked the question in January, while the proportion saying the country was heading in the wrong direction had fallen by seven points to 45%. Swing voters, who say they don’t know how they will vote or may yet change their minds, said “right direction” by 49% to 45%. While men said “right direction” by 52% to 43%, women said “wrong direction” by 47% to 45%.

**********

This week’s focus groups with undecided voters took place in Wirral West, where Esther McVey is facing a tough campaign to hold her seat. She is battling valiantly, according to our participants, and has made her presence felt consistently, not just at election times: “she seems to knock on my door practically every week”. Indeed all parties seem to have been active: “We often get those Focus leaflets from the Lib Dems. You know the sort of thing, a picture of a local councillor standing next to some dog poo.” But for all Esther’s virtues as a local MP, most said national issues would dominate their decision.

**********

Most people had not seen the seven-way leaders’ debates, and the format (“a bit too chaotic”) meant most of those who had did not feel they had learned much, other than that Nicola Sturgeon was “one to watch”. This was said with a mixture of admiration and suspicion. The SNP leader was generally seen as the most impressive performer, particularly by the women: “she took the lead”. But the prospect of her party taking a leading role in Westminster after the election was troubling for some, and the debate over Trident brought this into focus.

The issue had not been much on the minds of any of our participants, but nearly all found the prospect of weakening Britain’s nuclear defence disturbing: “It feels scary that we’ve got them but possibly even more scary if we don’t have them and other counties do”; “they’re expensive but we’ve got Russians coming into our air space and flying in our face… I wouldn’t trust Putin, would you?”

**********

Nobody spontaneously mentioned non-doms, though the subject had dominated the news the previous day (“was it in the Mail?”). Labour’s approach sounded right to the groups in principle, and nobody was shocked that Labour had proposed the policy or that the Tories had criticised it. When was the last time anyone could remember a politician saying or doing anything that surprised them? “When Margaret Thatcher burst into tears in the car when she was ousted.”

**********

The Greens Party’s boy-band broadcast, which some had seen (“don’t make me watch it again!”) provoked everything from broad smiles to frowns of bemusement, though many recognised the central argument that the main parties seemed depressingly similar. Still, this did not seem such a bad thing when they heard the list of what they regarded as wildly expensive and unrealistic Green proposals at the end, including nationalising the railways and scrapping tuition fees. “It gets your attention because it’s daft. But at the end when she says what they’re going to do, you know the only way to do it is to tax us to death… It’s all got to come from somewhere and it comes from us”. The threat was not unduly worrying, however: “They can say it because they haven’t got a cat in hell’s chance.”

**********

If the Greens (and UKIP) want the election to be about the same old parties versus outsiders who speak for the people, and the Conservatives want it to be about Cameron versus Miliband and competence versus chaos, and Labour want it to be about values, how did the groups characterise the choice at hand? Often it was about direction, or security versus risk. In general, this view of things favoured the Tories: “It’s about keeping us steady and not falling behind”; “they haven’t done everything right but they’re moving in the right direction.” But several who took this view were nonetheless uneasy about it, either because of particular policies they disliked or because they were just not comfortable with the idea of voting Conservative: “The Tories would probably keep the economy steadier but when it boils down to the individual bits and bobs, like tuition fees, you don’t like it”; “I did one of those anonymous survey things about which policies you prefer and surprisingly it said I should vote Tory. But I don’t know if I could.”

Most of these people would happily vote Labour were it not for the risk they thought was attached: “Values are nice but it can all go horribly wrong, can’t it?” Usually the risk was seen in economic terms: “In 2008 I was made redundant, in 2010 I became self-employed and things are going OK. I don’t want to go backwards”; “There is a lot flying around about wage rises, which we couldn’t afford. We’ve got two shops and lots of staff, and we’ve got to keep the business going.” And as one man put it, a previously Labour-voting retired panel beater, “the risk is Labour starting again as a sort of apprenticeship scheme. Cameron looks like he knows where he’s going.” But the economy was not the only risk with Labour: “There’s the Scottish problem. And… him.” What is the problem with “him”? “He just doesn’t look like a leader.” What does he look like, then? “Parker. The driver from Thunderbirds.”

The risks were not all in one direction, however, particularly if there was a chance the Tories could be governing on their own: “You’ve got to remember we’ve had a Conservative-Lib Dem coalition. If we just had the Conservatives they might be a bit more extreme.” One specific risk was the prospect of an EU referendum and its potential consequences: “The referendum worries me. It just creates a load of ill feeling and tension with Europe. It’s a gamble because the Conservatives are committed to that. It could end up like Scotland where everyone is blasé and then suddenly it’s ‘blimey, we might lose’.”

**********

But what if the leaders were to come over for dinner? An evening with Mr Farage would be amusing, and his conversation perhaps “a bit close to the bone”. They would cook him roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, or bangers and mash. Would he bring a gift? “A big pack of ciggies.” Mr Clegg would bring a bottle of Chablis (spontaneous unanimity across both groups on this point) and flowers. The groups would give him salmon (“pink and flaky”) or “a family barbecue to cheer him up”. Of the four, “he would be the most interested in your family, and would ask lots of questions”. Who would Mr Miliband bring with him? “Two advisers”. Would he bring a gift? “One of his advisers would have sorted something out.” His conversation would either be “very intense”, or “he would tell knock-knock jokes.” Mr Cameron would arrive “holding hands tightly” with Sam. Like his deputy he would enjoy a barbecue (though with steak, rather than the usual burgers and sausages), or something Italian, and would bring good red wine. The conversation? “You wouldn’t get an answer on anything serious but you could talk to him. He’s not a textbook Tory, not a pompous git.”