Like David Cameron, Ed Miliband has an election-winning coalition to build. And like the Prime Minister, he has a dilemma to go with it. Labour’s lead in the polls looks consistent, but is it firm? My latest research report, Project Red Alert, seeks to answer this question.

For many who have switched to Labour since 2010, buyer’s remorse is a big factor, especially if they simply voted for change, or liked David Cameron, but had not considered the likelihood of cuts. Not surprisingly, this is even more the case among those for whom austerity has brought personal consequences.

Like many other voters, the feature of the Labour Party they most often mention spontaneously is that it is for the working class – unlike the Tories, who are for the better off. (The fact that this is often said by people who both regard themselves as working class and voted Conservative at the last election probably says as much about the strength of the Labour brand as it does about the caprice of voters).

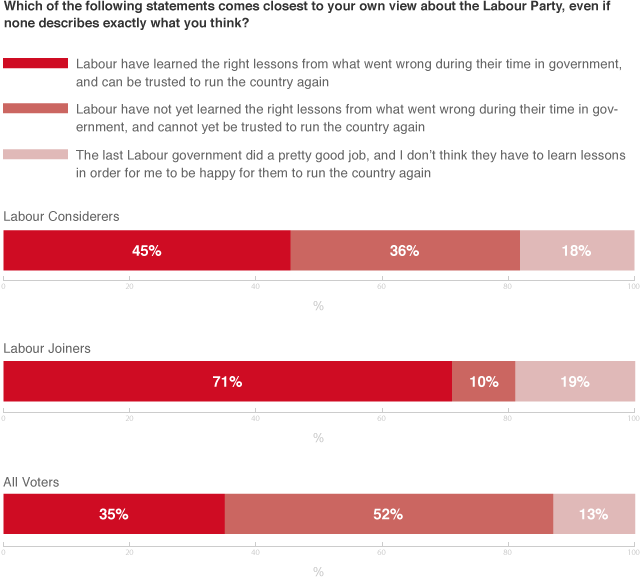

Labour Joiners recount a litany of things that have changed since 2010. Significantly, the Labour Party is never among them. Though a majority of Joiners said in the poll that they thought Labour had learned the right lessons from its time in government, much of this is wishful thinking: in discussion, they struggle to think of any evidence that Labour has changed or learned, often insisting simply that “they must have done”.

Many Joiners hit by austerity hope a new Labour government would restore some or all of what they have lost out on. It would be dangerous for Labour to rely on this impression: this kind of fantasy rarely survives a general election campaign.

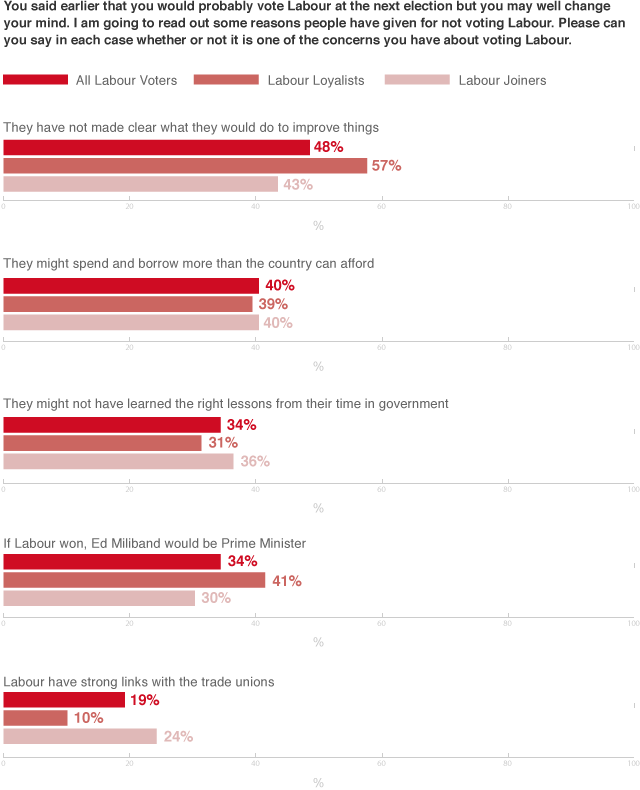

A quarter of those who have switched to Labour say they have not finally decided and may well change their minds. Of these “soft Joiners”, four in ten say one of the concerns they have about voting Labour is that they might spend and borrow more than the country could afford.

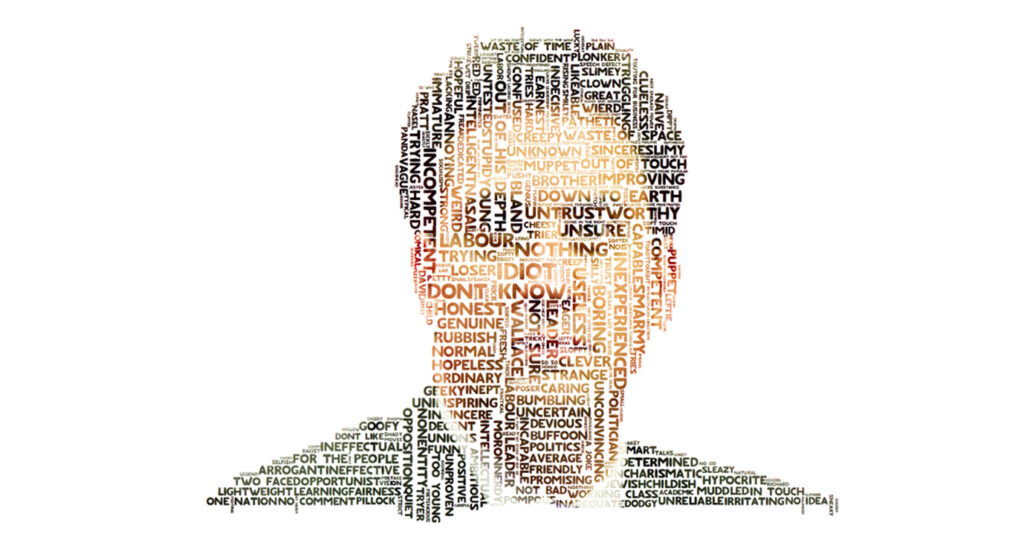

A further 10% of all voters are Labour Considerers, who would not vote Labour tomorrow, but may do so in future. Notably, a low to neutral view of Ed Miliband is the factor that most distinguishes this group. While not an attraction for Joiners (who often say he is the price to be paid for a Labour government, as do some Loyalists), he is a factor preventing some people from switching to Labour. If this were not the case, Labour’s poll share would be above 50%.

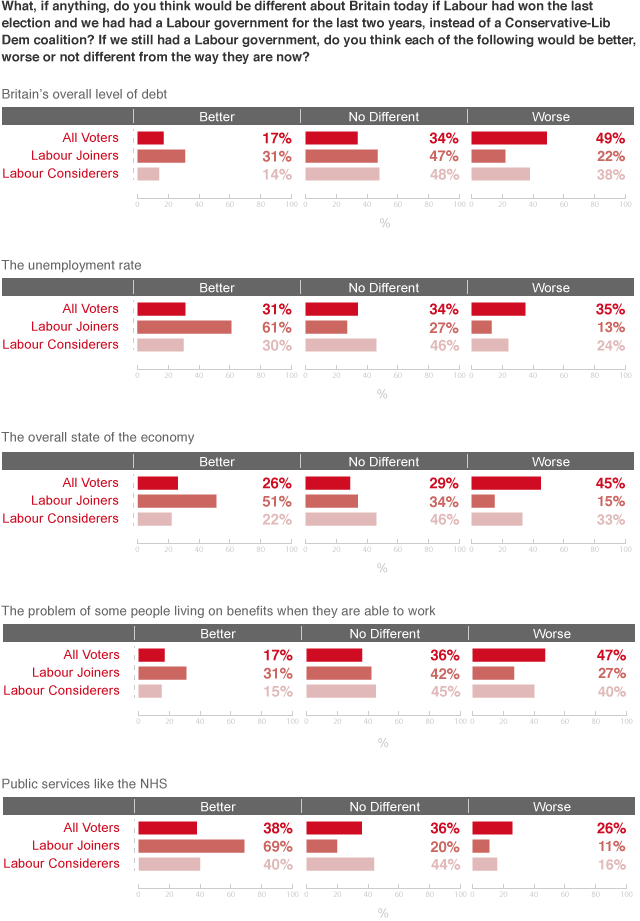

Considerers are much less ready to say that Labour can be trusted to govern again. Asked what would be different today had Labour won the last election, they say they would have carried on spending and borrowing, perhaps with disastrous consequences. Labour’s opposition to cuts, and apparent refusal to take responsibility for the state of the public finances when they left office, only reinforce this view.

With its double-digit poll lead, Labour may decide it need not broaden its appeal any further. This would be a gamble. The wild card is the economy. Even some Joiners say they would have to think again in the event of a tangible recovery. Having so vehemently opposed the Conservative economic strategy, Labour had better be sure it is not going to work. If it does, many will have to conclude that the Tories were right and Labour were wrong.

For Labour, creating a more stable voting coalition means restoring credibility on the economy, especially the deficit. Some in the Labour movement argue that by talking about the deficit the party can only lose, since it is a Tory issue: they should “frame” the debate in terms more favourable to themselves. But the deficit is not something the Conservatives have invented in some sinister “framing” exercise of their own. It is all too real, a fact recognised by many of the voters Labour needs. The party has no chance with people who think it wants to shy away from the central economic question of the day.

All of this means that Ed Miliband has a choice. He can either make clear to his supporters that there will be no return to the days of lavish spending, or he can fight an election knowing that most voters do not believe Labour have learned their lessons, and that many of his potential voters fear Labour would once again borrow and spend more than the country can afford.

If he makes the wrong choice, Miliband will be gambling on a precarious coalition of the disaffected and the dependent who do not see, or do not want to see, the economic reality that the post-2015 government will have to face. Perhaps he thinks it would be better to wait until he is in Number Ten to disappoint them – in which case he will miss out on voters who want some reassurance that Labour will not return to form, and could miss out on Number Ten altogether.

The fact that Labour have got themselves into this position shows how much the party has changed since it was last in opposition. Tony Blair would never have risked losing because voters feared a Labour government would be profligate.

I think this research clearly shows the strategic path Labour should choose.

But why would they take advice from me?